Is Groundwater the answer?

Groundwater development has proved integral in fuelling agricultural growth all over the Global South, most notably Asia. As a result, groundwater in South Asia now supplies over half of the irrigation supplies. Unfortunately, Sub-Saharan Africa missed this Groundwater Revolution. However, recently there has been an increase in farmer-led irrigation methods utilising groundwater. This shows that perhaps the tide is turning. Thus, I will seek to show Africa's groundwater extraction potential and how this could help its agriculture.

Africa sits upon a vast water reserve. Sub-Saharan Africa has such a large reserve that it is estimated it has over 3 times more groundwater availability per capita than China and almost 6 times more than India. This groundwater source is quantified as being roughly 0.66 million km³. To show the magnitude of this figure, lets compare it to these outputs below:

- Average annual rainfall is estimated at 0.02 million km³,

- Renewable freshwater sources roughly reach 0.004 million km³,

- Lake storage totals 0.03 million km³

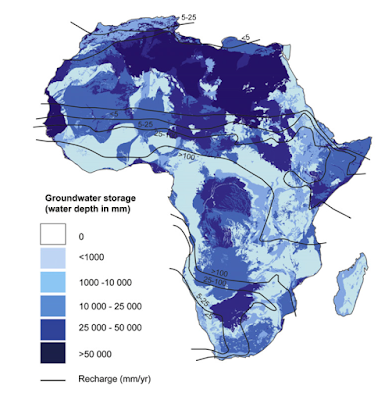

The total of these values only reached 0.054 million km³. This means if Africa's immense groundwater supply was utilised, total water availability would more than double, showing the clear potential available here. Common water scarcity metrics often portray Africa as being a continent in water stress. Indexes such as the Water Stress Index (WSI) and Withdrawal-to-Availabilty (WTA) often exclude groundwater potential from their measures. Instead, they focus on using annual mean river runoff as the measure for freshwater availability. Therefore, this exclusion makes the continent seem increasingly more water insecure that it actually is. Figure 1 showcases just how much untapped groundwater potential there is- particularly in North, Central and South Africa. This works to negatively portray Africa as water scarce when they actually have a plethora of sources that just require development to gain access. Can it be said that the exclusion of groundwater potential from global indexes contributed to the negative portrayal of Africa's future water and food security? A rethink of how water security is measured is needed to stop the narrative that Africa and the Global South are supposedly 'inferior' and in need to aid from the Global North.

However, this figure of 0.66 million km³ of groundwater potential can be misleading. In fact, only around 692- 1644km³ is used yearly for irrigation. This shows that despite its great potential, a lot of investment and development is needed to allow full potential to be reached. Additionally, this renewable groundwater is spatially limited. The groundwater is unequally distributed. More than half the supply goes to only 4 countries (Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Congo and Cameroon). The others do not benefit.

Despite this, groundwater utilisation for irrigation is seen as a necessity to maintain water supplies and food security. This has been done by renewable and non-renewable groundwater systems. Below, I will focus on the non-renewable systems used in Africa.

Fossil Aquifers: Nubian Sandstone Aquifer

If you take a minute to quickly scroll up and take another look at Figure 1, you can clearly see that a vast majority of the groundwater is located underneath the Sahara Desert in the northeast. Covering a distance of over 2.2 million km², this aquifer is located beneath Sudan, Egypt, Libya and Chad. Due to the growing demand for water and lack of freshwater availability in this area, there has already been over 40 billion km3 of water abstracted. This has been done solely by Libya and Egypt and has resulted in a 60m decline of the aquifer's maximum water level, impacting all countries that lie above it. This decline means that extraction subsequently becomes more expensive as deeper wells must be dug.

Moreover, abstraction can result in the direction of groundwater flows changing. Abstracting from one area, i.e. upstream, means the water downstream is reduced. This impacts the countries downstream and can lead to political conflicts occurring as they all want greater water flow. Additionally, saltwater intrusion can occur due to abstraction near coastal areas. This results in the source becoming saline, rendering it useless for irrigation. Due to the many impacts that groundwater abstraction can cause, co-operating between countries is essential. This leads to the usage of the 'law of transboundary aquifers', which dictates that every affected country has sovereignty over the parts located within its territory. It also specifies that these Aquifer states must utilise the source reasonably and equitably.

Concluding Thoughts

Hopefully this blog has conveyed just how water rich Africa truly is. The spatial distribution of the groundwater is unequal however. Despite this, many countries in Africa could be reclassified as not being water-scarce if groundwater was included in the indexes. Thus, this shows the importance and impact that groundwater can have in ensuring food security via irrigation.

However, transboundary conflicts must be avoided to ensure equitable use of non-renewable resources. Next week, renewable groundwater systems will be analysed.

Good engagement with literature, referencing is good and overall presentation of thought is well laid out. The only point i will raise is that picking a case study country or region to explore question or issue of groundwater could be better, as a focus across a huge continent can be a challenge.

ReplyDelete